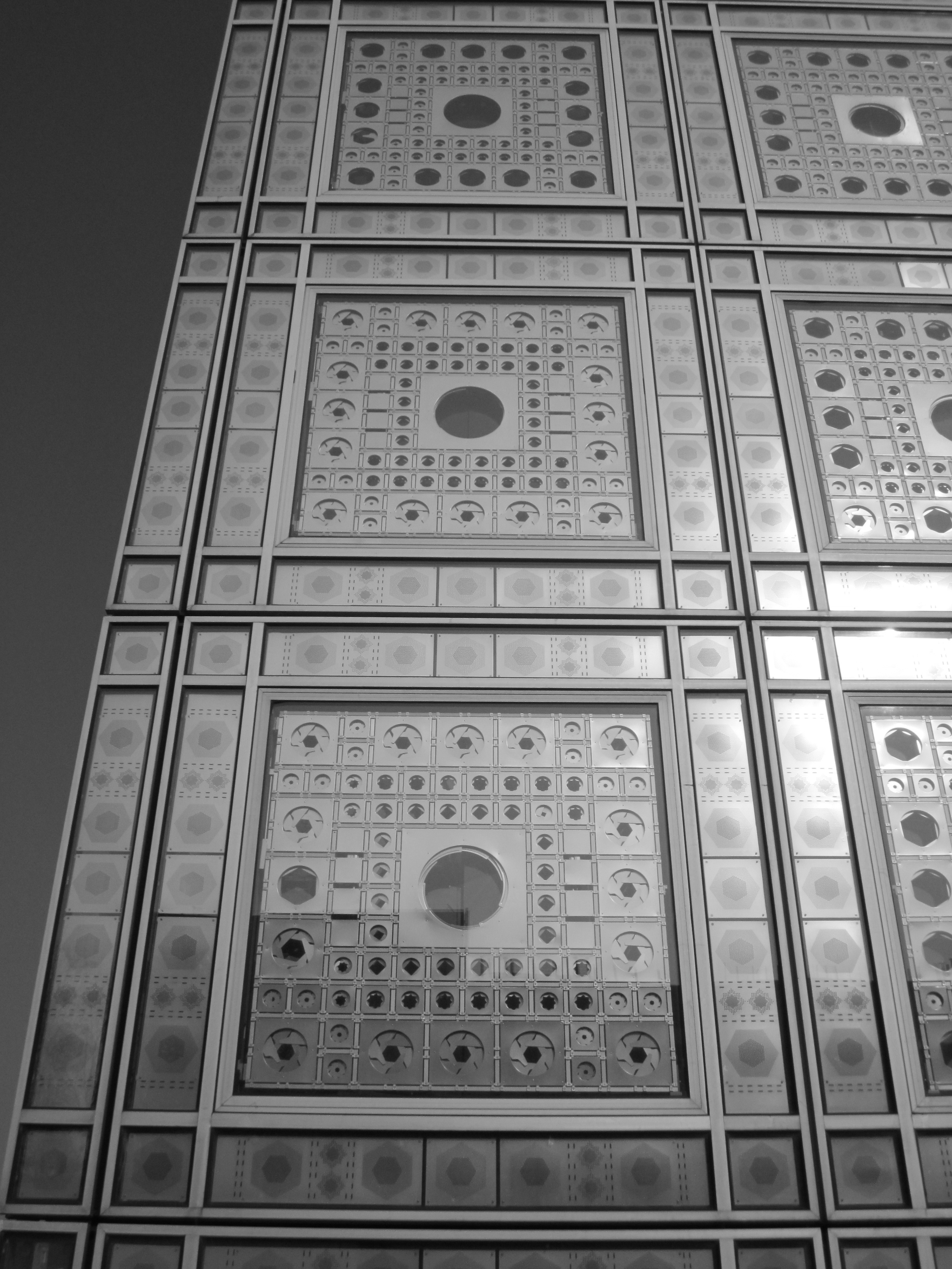

I have always loved making jewellery that plays with scale and form. Perhaps being an engineer's daughter explains the way I perceive the world around me and why I am attracted to designs that echo the strong clean lines found in modern architecture and engineering. Many people are amused by my fascination with the ways that buildings and bridges are held together and the forms they create. If they stop, and look closely at the simplicity of an oversized bottle screw connecting cables of a suspension bridge to its deck, or look up in an airport at the shapes formed by roof struts supporting a free span roof I think most people are impressed by the engineering behind them. For me, good architecture is about how humans interact with their surroundings as well as the structure's form. I find it interesting that we are usually constrained to interacting with the spaces within an architectural structure rather than with the structure itself. By shrinking the same geometric forms to the scale of the human body and abstracting them somewhat, the nature of the interaction is dramatically changed. In my jewellery it is the structural elements that the wearer interacts with. The spaces are only observable, being too small to inhabit.

first saw rapid prototyping more than 10 years ago when I visited an engineering trade show with my father. The show was all very serious engineering, focussing mostly on large scale machinery and techniques designed to work with steel and other materials on an industrial scale. I got very excited though by all of the machinery and baffled a lot of the salesmen by asking them about the smallest, most delicate objects their tools could create. I wasn’t at all impressed by how fast they could operate or how many axes they had.

I felt like I had finally started to understand how I could bring some of my most intricate designs to life with the possibilities offered by 3D printing.

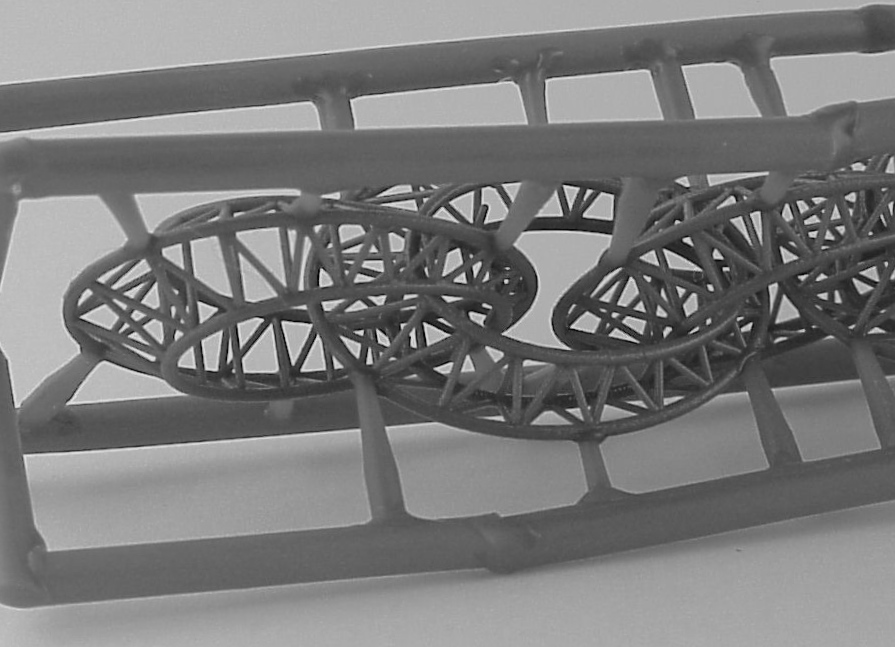

Despite its obvious potential for creating complex forms, 3D printing at the time was barely able to cope with the fine scale my designs needed. It was only with a significant amount of experimentation with distributors of some of the first wax printers in the country that I was able to take my first design all the way from concept to solid gold! We really were pushing the limits of what was possible at the time. The technology is now far more advanced and, although it's still far from straightforward, usually I know in advance whether it will be possible to create one of my designs.

I begin in the traditional way, with paper sketches or a maquette of the main design. Early in the life of the design I start to draw a three dimensional computer model using CAD software. It's at this stage that the final form and scale emerge; as I translate a picture in my mind into something complete and tangible and I'm forced to think through the practicalities of how to actually create the piece. Even now, with improved technology and more knowledge the more intricate designs are technically challenging to create.

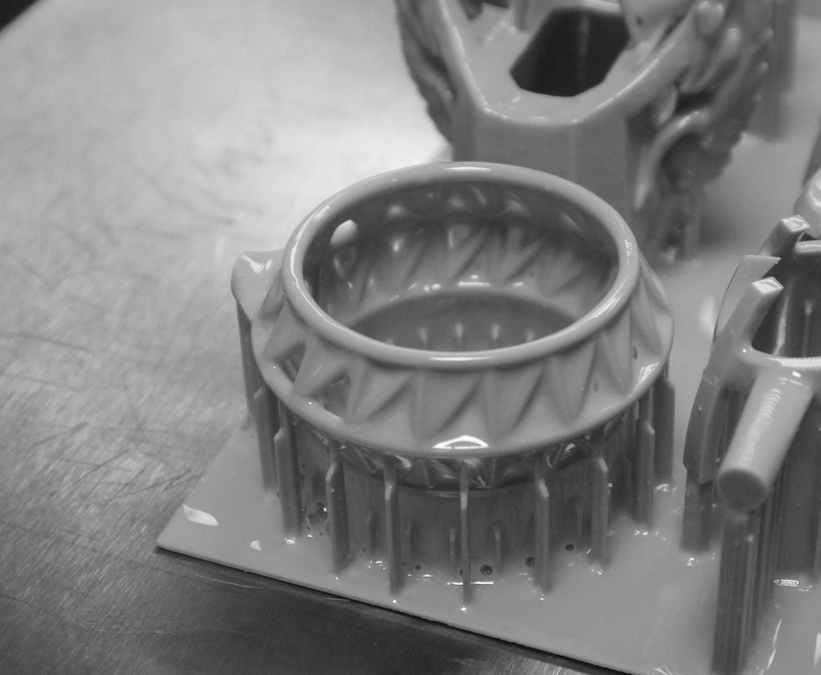

One of the most important design considerations, and vital to get right, is how solid gold or metal will flow during the casting process to ensure a complete and even final piece. How molten gold flows in a complex shape is the major factor which dictates how complex the piece can be and where I need to place casting sprues (temporary structures that allow liquid gold to be injected into the piece).

Every piece I make, for every design is created in the same way. The first incarnation of the design is a fully formed wax model that exactly matches the final gold piece. The wax model is built up in thousands of thin layers of wax, each about twice the thickness of a human hair. It sounds like a slow process, and it is. Creating the wax model for one of my larger necklaces can take 100 hours of continuous machine time.

Once complete, the wax model is embedded in a fireproof material and turned into solid gold by injecting pressurised molten metal into the model. Gold replaces the wax, taking on the form of the final piece. The supporting material is dissolved away to leave just the solid gold piece of jewellery, albeit still needing a lot of finishing before it can be worn.

I clean up the cast and then polish it, mostly using techniques that haven't much changed in hundreds of years. At the end I have a gleaming gold piece of jewellery that perfectly matches the image in my mind many weeks before. Even though I understand in great detail how it is all possible I am still amazed at the end of each piece that a process so complex can even work. It really is a testimony to our engineering ingenuity.

To be showcasing my jewellery at the Goldsmiths Fair is very exciting. I remember my very first visit to the show and being in awe of the quality of work on display and of the history represented by the Goldsmiths hall itself. I know visitors will be intrigued by my designs and I am looking forward to their puzzlement as they try to work out how my more complex pieces are made.